# Goner and Dependency Injection

# Definition of Goner

In the Gone application, all components are required to be defined as Goners (i.e., structures that "inherit" gone.Flag, although Go does not have the concept of "inheritance" as seen in other languages; instead, it uses anonymous embedding). If a property of a Goner is tagged with the gone:"" tag, the Gone framework will attempt to automatically wire this property. Here's an example of defining a Goner:

package example

import "github.com/gone-io/gone"

type AGoner struct {

gone.Flag

}

Injecting the above-defined AGoner into another Goner:

package example

import "github.com/gone-io/gone"

type BGoner struct{

gone.Flag

A *AGoner `gone:"*"` // The purpose of the gone tag is to inform Gone that this property needs to be automatically injected with a value

}

In this example, both the injected and the injecting structures must be Goner (i.e., structures embedded with gone.Flag). The gone:"*" tag on the A property of the BGoner tells the framework that this property needs to be injected with a value.

# How Dependency Injection is Achieved in Gone

In Java Spring, classes are annotated with @Component, @Service, etc., and during Spring startup, these specially annotated classes are automatically scanned, instantiated, and their annotated properties injected with corresponding values.

The reason Spring can achieve this functionality lies in a critical feature of Java: after Java code is compiled into a JAR file, all class bytecode is preserved, even for classes not directly dependent on the main function. However, in Go, the compiled code is pruned, and only the code relevant to the main function is retained in the binary. Therefore, if we merely define Goners, we'll find that our Goner code has been pruned.

How do we prevent our Goners from being pruned? The answer is simple: explicitly add all Goners to a "repository". In Gone, this repository is called the Cemetery. Goner means "deceased", and Cemetery is the graveyard used to bury (Bury) Goners. We can instantiate all Goners and add them to the Cemetery at program startup:

package main

import "example"

import "github.com/gone-io/gone"

func main() {

gone.Run(func(cemetery gone.Cemetery) error {

cemetery.Bury(&example.AGoner{})

cemetery.Bury(&example.BGoner{})

return nil

})

}

In the above code, we see that gone.Run can accept a function in the form of func (cemetery gone.Cemetery) error. In practice, this function, which we call Priest, is responsible for burying Goners in the cemetery.

# How to Execute Business Code in Goners?

In Gone, we've made an interesting definition: when all properties of a Goner are injected, we say that this Goner has been resurrected (Revive). If you look at the source code of Gone, you'll find that the component responsible for managing the revived Goner status is called Heaven, inspired by the mythical belief across religions that people ascend to heaven after death.

To execute business code in Goners, we can define a method on Goners called AfterRevive() gone.AfterReviveError. This method is executed after a Goner is Revived, and Goners possessing this method are called Prophets. In practice, we typically only need to define a small number of prophets to guide code execution.

Here's an example; you can find the code here (opens new window):

package main

import "github.com/gone-io/gone"

type Adder struct {

gone.Flag

}

func (a *Adder) Add(a1, a2 int) int {

return a1 + a2

}

type Computer struct {

gone.Flag

adder Adder `gone:"*"`

}

func (c *Computer) Compute() {

println("I want to compute!")

println("1000 add 2000 is", c.adder.Add(1000, 2000))

}

// AfterRevive is a function executed after revival.

func (c *Computer) AfterRevive() gone.AfterReviveError {

// boot

c.Compute()

return nil

}

func main() {

gone.Run(func(cemetery gone.Cemetery) error {

cemetery.Bury(&Computer{})

cemetery.Bury(&Adder{})

return nil

})

}

Executing the above code will yield the following result:

Revive github.com/gone-io/gone/heaven

Revive github.com/gone-io/gone/cemetery

Revive main/Computer

Revive main/Adder

I want to compute!

1000 add 2000 is 3000

# The gone Command: Automatically Generating Priest Functions

In fact, we've already covered the core functionality of the Gone framework. However, due to limitations in Golang itself, we can't achieve the same level of convenience as Spring, where all Goners need to be manually buried (**Bury**ed) into the Cemetery. To make Gone easier to use, we've developed a utility tool to automatically generate Priest functions. Below, we'll explain how to use this utility tool in a project.

You can find the complete code here (opens new window)

# 1. Install the Utility Tool: gone

The utility tool, also named gone, can be installed using go install as follows:

go install github.com/gone-io/gone/tools/gone@latest

For more information on using the gone command, please refer to the gone utility tool documentation (opens new window).

# 2. Create a New Project Named gen-code

mkdir gen-code

cd gen-code

go mod init gen-code

# 3. Create Goners

File: goner.go

package main

import "github.com/gone-io/gone"

//go:gone

func NewAdder() gone.Goner {

return &Adder{}

}

//go:gone

func NewComputer() gone.Goner {

return &Computer{}

}

type Adder struct {

gone.Flag

}

func (a *Adder) Add(a1, a2 int) int {

return a1 + a2

}

type Computer struct {

gone.Flag

adder Adder `gone:"*"`

}

func (c *Computer) Compute() {

println("I want to compute!")

println("1000 add 2000 is", c.adder.Add(1000, 2000))

}

// AfterRevive is a function executed after revival.

func (c *Computer) AfterRevive() gone.AfterReviveError {

// boot

c.Compute()

return nil

}

In the code above, please note that we've added two factory functions NewAdder() gone.Goner and func NewComputer() gone.Goner, and we've put a special comment before the functions:

//go:gone

Please do not remove this comment, as it tells the utility tool how to generate the code.

# 4. Use the Utility Tool

Please execute the following command in the gen-code directory:

gone priest -s . -p main -f Priest -o priest.go

This command scans the current directory and generates a priest function with the function name Priest, in the package named main, and puts the code in a file named priest.go.

After executing the command, a file named priest.go will be generated in the current directory with the following content:

// Code generated by gone; DO NOT EDIT.

package main

import (

"github.com/gone-io/gone"

)

func Priest(cemetery gone.Cemetery) error {

cemetery.Bury(NewAdder())

cemetery.Bury(NewComputer())

return nil

}

# 5. Add a main Function

File: main.go

package main

import "github.com/gone-io/gone"

func main() {

gone.Run(Priest)

}

Now, we've completed the entire small Gone program. Its file structure is as follows:

.

├── go.mod

├── go.sum

├── goner.go # Definition of goners

├── main.go

└── priest.go # Generated code

You can run the program using the command go run ., and the program will output the following:

Revive github.com/gone-io/gone/heaven

Revive github.com/gone-io/gone/cemetery

Revive main/Adder

Revive main/Computer

I want to compute!

1000 add 2000 is 3000

# Anonymous Injection vs Named Injection

In the preceding sections, all of our examples have demonstrated anonymous injection by type. When injecting anonymously, if there are multiple Goners of the same type, only one will be injected, typically the first one that was revived. Gone also supports named injection, or named burial.

Firstly, let's take a look at the complete definition of the Cemetery.Bury function: Bury(Goner, ...GonerId) Cemetery. This definition serves two purposes:

- It supports named burial, where the second parameter is optional, allowing you to pass a string as the ID (GonerId) of the Goner.

- It supports chaining of the Bury function.

# Named Burial

To achieve named burial, our code can be written like this:

// Priest Responsible for putting Goners that need to be used into the framework

func Priest(cemetery gone.Cemetery) error {

cemetery.

Bury(&AGoner{Name: "Injected Goner1"}, "A1"). // Burial of the first AGoner, ID=A1

Bury(&AGoner{Name: "Injected Goner2"}, "A2"). // Burial of the second AGoner, ID=A2

Bury(&BGoner{})

return nil

}

Alternatively, you can decouple the construction of Goners from their burial like this:

// NewA1 constructs A1 AGoner

func NewA1() (gone.Goner, gone.GonerId) {

return &AGoner{Name: "Injected Goner1"}, "A1"

}

// NewA2 constructs A2 AGoner

func NewA2() (gone.Goner, gone.GonerId) {

return &AGoner{Name: "Injected Goner2"}, "A2"

}

// Priest Responsible for putting Goners that need to be used into the framework

func Priest(cemetery gone.Cemetery) error {

cemetery.

Bury(NewA1()).

Bury(NewA2()).

Bury(&BGoner{})

return nil

}

Next is the named injection within structs, which can be better understood with an example:

type BGoner struct {

gone.Flag // Tell the framework that this struct is a Goner

a *AGoner `gone:"*"` // Anonymous injection of an AGoner

a1 *AGoner `gone:"A1"` // Named injection of A1

a2 *AGoner `gone:"A2"` // Named injection of A2

}

Note: In the code above, the tag after the struct field:

gone:"*"denotes anonymous injection.gone:"A1"denotes injection with the IDA1.

In Go, whether anonymous or named, the Goner to be injected must be type-compatible; otherwise, the injection will fail.

# Pointer Injection, Value Injection, and Interface Injection

If the property of the injected struct is a pointer, then the injection is called pointer injection. The definitions for value injection and interface injection are similar. Let's take an example:

type AGoner struct {

gone.Flag // Tell the framework that this struct is a Goner

Name string

}

func (g *AGoner) Say() {

println("I am the AGoner, My name is", g.Name)

}

type Speaker interface {

Say()

}

type BGoner struct {

gone.Flag // Tell the framework that this struct is a Goner

a0 *AGoner `gone:"*"` // Anonymous injection of an AGoner; pointer injection

a1 *AGoner `gone:"A1"` // Named injection of A1; pointer injection

a2 AGoner `gone:"A1"` // Value injection

a3 Speaker `gone:"A2"` // Interface injection

}

In the code above, BGoner.a0 and BGoner.a1 are subjected to pointer injection. BGoner.a2 is subjected to value injection, while BGoner.a3 is subjected to interface injection.

A special note: In Go, "assigning or passing a value type involves making a copy." This means that when using value injection, a new "object" is actually created, and the new and old objects are only equal at the moment of transfer. They are independent in memory. This can lead to some unexpected results. For example:

type BGoner struct {

gone.Flag

a1 AGoner `gone:"A1"` // Value injection

a2 AGoner `gone:"A1"` // Value injection

}

func (g *BGoner) AfterRevive() gone.AfterReviveError {

g.a1.Name = "dapeng"

g.a2.Name = "wang"

fmt.Printf("a1 is eq a2: %v", g.a1 == g.a2)

return nil

}

In the code above, BGoner.a1 and BGoner.a2 are both injected with the same Goner (A1). However, since it's value injection, during the injection process, the framework can only copy the value of A1 Goner to BGoner.a1 and BGoner.a2. After injection, BGoner.a1 and BGoner.a2 have no connection with A1, and there's no connection between BGoner.a1 and BGoner.a2. There will also be three separate spaces in memory occupied by AGoner type. The result of fmt.Printf("a1 is eq a2: %v", g.a1 == g.a2) will be false.

Considering that Gone is primarily intended as a foundational framework, we have retained the value injection feature. However, in most cases, we recommend using pointer injection and interface injection.

# Pointer Injection vs Interface Injection

During the Bury process of Goner, it's required to pass a reference. This means that the first parameter of the Cemetery.Bury method must be of a reference type. Both pointer injection and interface injection can pass the reference of Bury to the properties of a struct. Pointer injection is straightforward and intuitive, with a one-to-one correspondence between types, requiring little explanation.

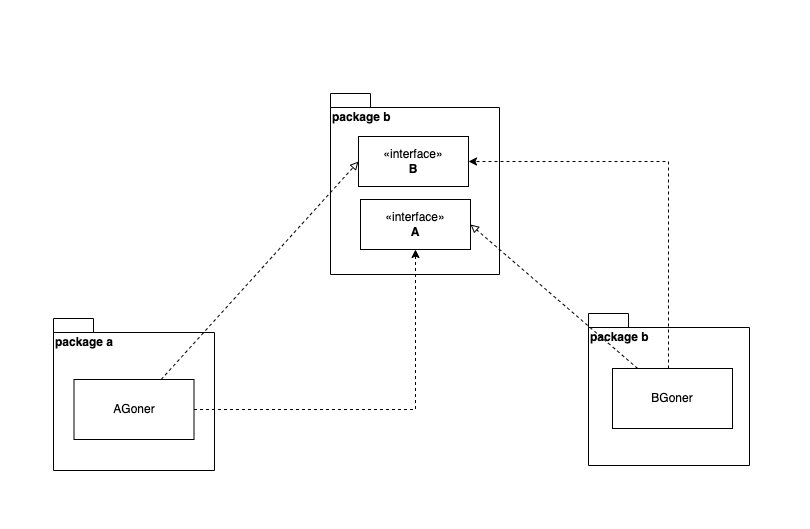

Interfaces are one of the most essential designs in Go. Their purpose is to decouple the business usage from the implementation logic, allowing users of the interface to not be concerned with the implementation details. Another purpose of interfaces is to break circular dependencies. If two modules have a circular reference and they are in different packages, it violates the rule of no circular dependencies in Go, leading to compilation failure. We can use interfaces to break this circular dependency.

Circular dependency:

Using interfaces to break circular dependency:

Using interfaces can hide the implementation details of business logic, effectively reducing the coupling between modules and better adhering to the "open-closed" principle. Therefore, we recommend using interface injection. However, there are no absolutes in everything, introducing interfaces will certainly increase additional costs, so we still support pointer injection.

# Slice Injection and Map Injection

Gone supports injection into Slice and Map, meaning it supports the following syntax:

type BGoner struct {

gone.Flag

aSlice1 []*AGoner `gone:"*"` // Injected property is a slice of Goner pointers

aSlice2 []AGoner `gone:"*"` // Injected property is a slice of Goner values

aMap1 map[string]*AGoner `gone:"*"` // Injected property is a map of Goner pointers

aMap2 map[string]AGoner `gone:"*"` // Injected property is a map of Goner values

}

The rules for injection are as follows:

- The element type of Slice and Map can be Goner pointer type or Goner value type, or an interface.

- Gone will inject all types compatible with Goner into Slice and Map.

- The type of Map key can only be string.

- The value of Map key is the GonerId of the injected Goner. If no GonerId is specified when burying an anonymous Goner, Gone will generate one automatically.

WARNING

Using values as the element types for Slice and Map is not recommended.

Here's a complete example:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"github.com/gone-io/gone"

)

type AGoner struct {

gone.Flag // Tell the framework that this struct is a Goner

Name string

}

func (g *AGoner) Say() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("I am the AGoner, My name is: %s", g.Name)

}

type BGoner struct {

gone.Flag

aSlice1 []*AGoner `gone:"*"` // Injected property is a slice of Goner pointers

aSlice2 []AGoner `gone:"*"` // Injected property is a slice of Goner values

aMap1 map[string]*AGoner `gone:"*"` // Injected property is a map of Goner pointers

aMap2 map[string]AGoner `gone:"*"` // Injected property is a map of Goner values

}

// AfterRevive executed After the Goner is revived; After `gone.Run`, gone framework detects the AfterRevive function on goners and runs it.

func (g *BGoner) AfterRevive() gone.AfterReviveError {

for _, a := range g.aSlice1 {

fmt.Printf("aSlice1:%s\n", a.Say())

}

println("")

for _, a := range g.aSlice2 {

fmt.Printf("aSlice2:%s\n", a.Say())

}

println("")

for k, a := range g.aMap1 {

fmt.Printf("aMap1[%s]:%s\n", k, a.Say())

}

println("")

for k, a := range g.aMap2 {

fmt.Printf("aMap2[%s]:%s\n", k, a.Say())

}

return nil

}

// NewA1 creates A1 AGoner

func NewA1() (gone.Goner, gone.GonerId) {

return &AGoner{Name: "Injected Goner1"}, "A1"

}

// NewA2 creates A2 AGoner

func NewA2() (gone.Goner, gone.GonerId) {

return &AGoner{Name: "Injected Goner2"}, "A2"

}

func main() {

gone.Run(func(cemetery gone.Cemetery) error {

cemetery.

Bury(NewA1()).

Bury(&AGoner{Name: "Anonymous"}).

Bury(NewA2()).

Bury(&BGoner{})

return nil

})

}

The example yields the following result upon execution:

Revive github.com/gone-io/gone/heaven

Revive github.com/gone-io/gone/cemetery

Revive main/AGoner

Revive main/AGoner

Revive main/AGoner

Revive main/BGoner

aSlice1:I am the AGoner, My name is: Injected Goner1

aSlice1:I am the AGoner, My name is: Anonymous

aSlice1:I am the AGoner, My name is: Injected Goner2

aSlice2:I am the AGoner, My name is: Injected Goner1

aSlice2:I am the AGoner, My name is: Anonymous

aSlice2:I am the AGoner, My name is: Injected Goner2

aMap1[A1]:I am the AGoner, My name is: Injected Goner1

aMap1[main/AGoner#1374393662624]:I am the AGoner, My name is: Anonymous

aMap1[A2]:I am the AGoner, My name is: Injected Goner2

aMap2[A2]:I am the AGoner, My name is: Injected Goner2

aMap2[A1]:I am the AGoner, My name is: Injected Goner1

aMap2[main/AGoner#1374393662624]:I am the AGoner, My name is: Anonymous

# Private Property Injection

Following the "Open-Closed Principle," attributes that modules depend on should ideally be private. Gone supports injecting into private variables of a struct.